Higher Education and Teaching

For over a decade, I taught a wide spectrum of classes at New York University, Rutgers, and Barnard College. My courses included instruction in German language, philosophy, literature, media studies, and political theory for an average of 30 students in 2 courses per semester. I designed my own course syllabi, lesson plans, essay assignments, quizzes, and written and oral exams, while developing metrics to assess the effectiveness of pedagogical strategies and curricula and adjusting based on results. My years of interaction with students in the classroom heavily influences my approach to eLearning — in both asynchronous and hybrid modalities.

You can read about my teaching philosophy below!

Learning Materials

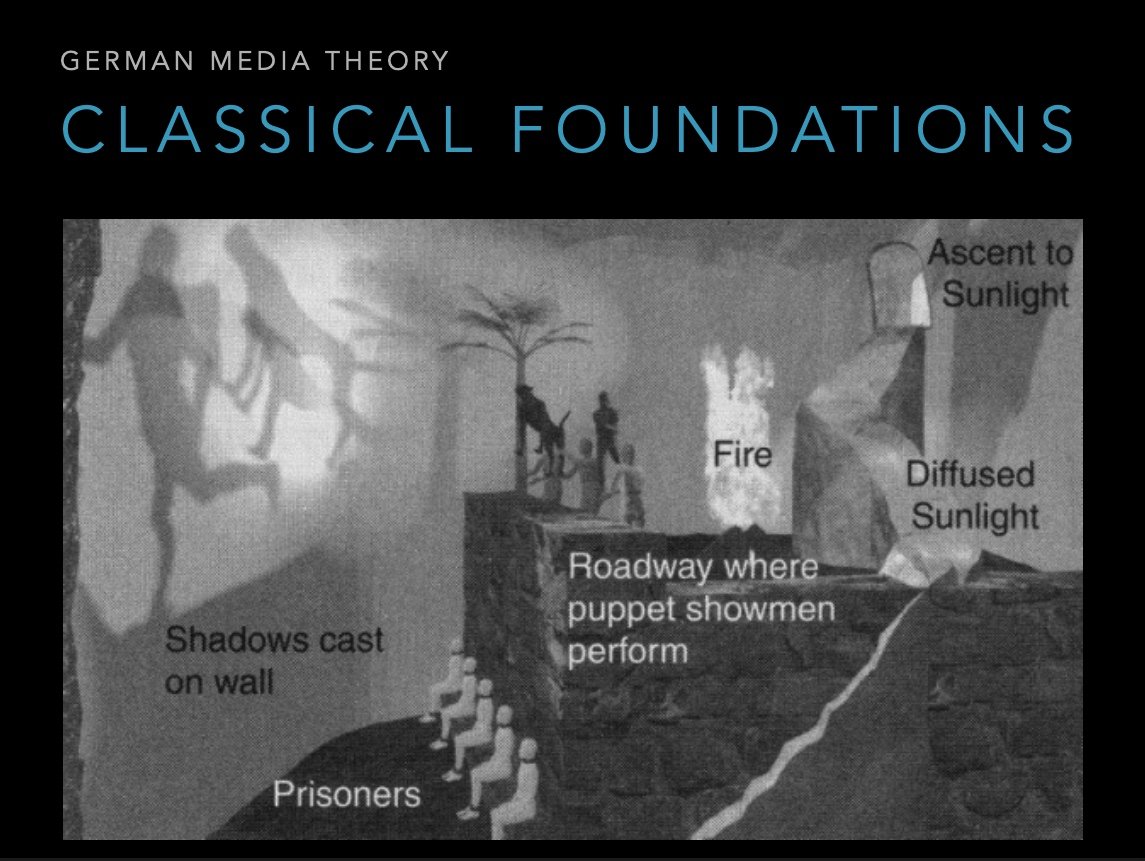

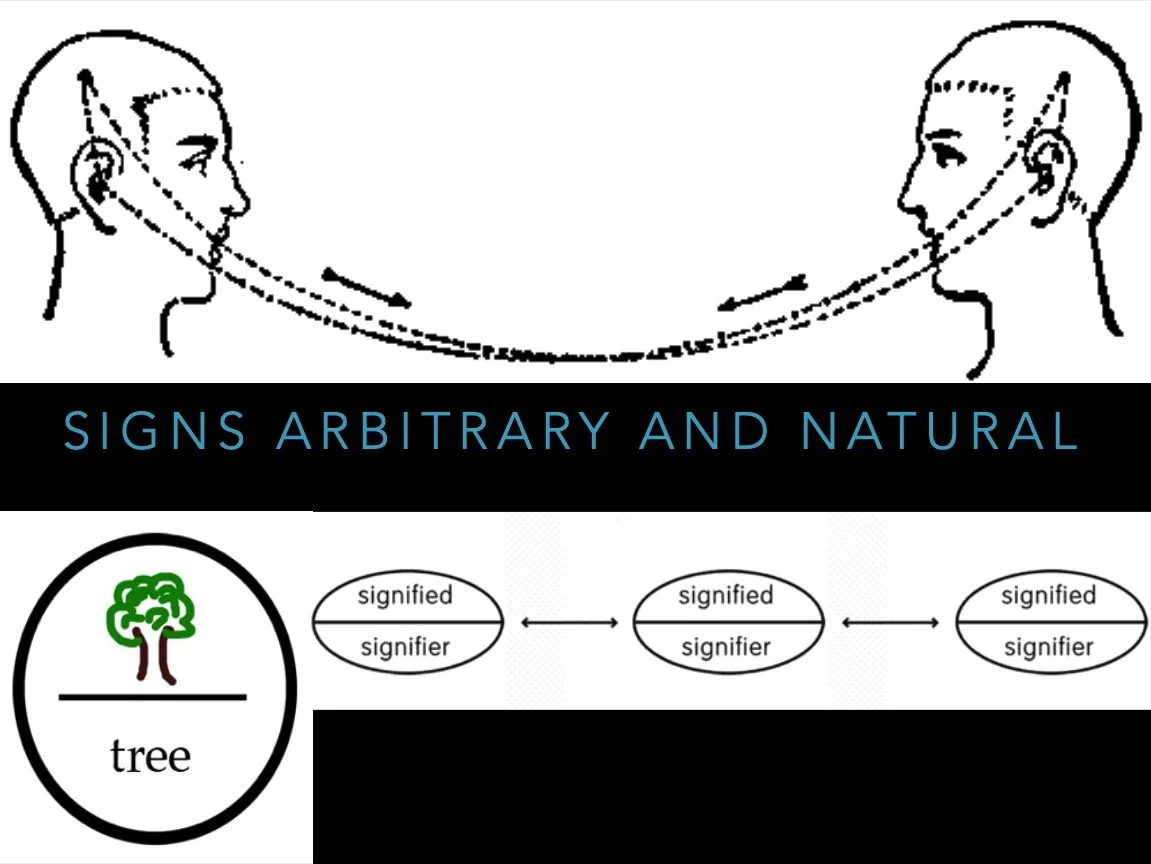

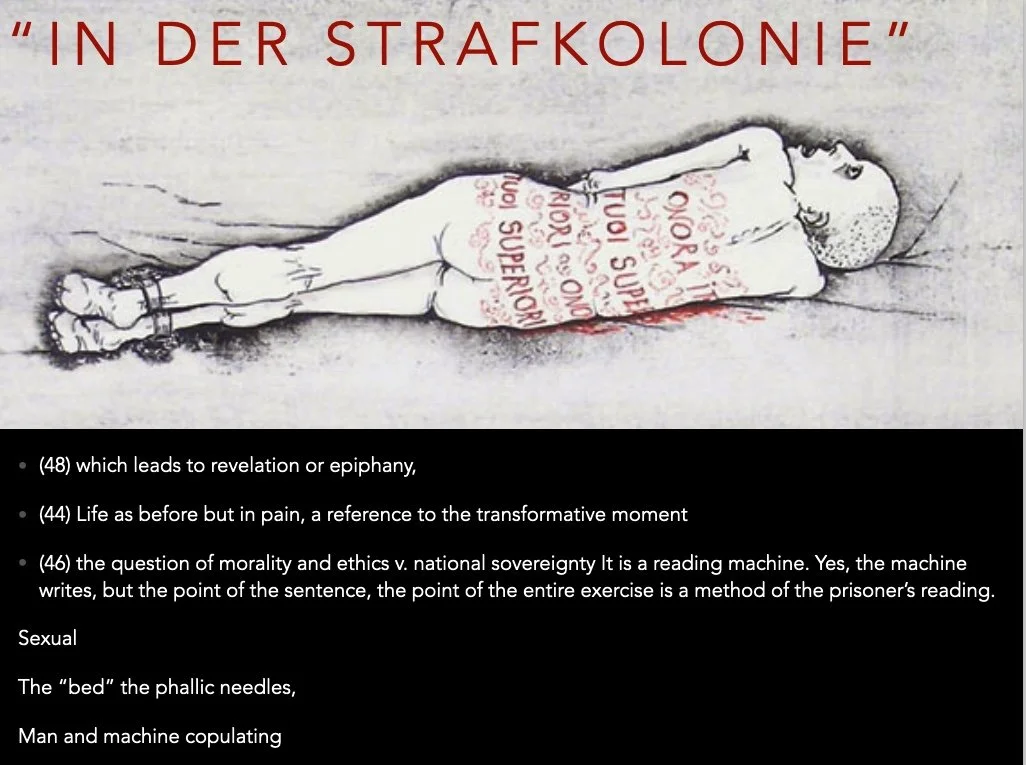

Part of my teaching involved making engaging learning packages for my students that both draw them into the topic, make it relatable, and provide a smooth entry point to difficult concepts.

Syllabi

I have three north stars for my approach to my course design in the university classroom setting: to make seemingly dusty topics and themes relevant, to break complicated and sometimes obtuse concepts into understandable blocks, and/or demonstrate the use of a foreign language in its natural, cultural context.

NOTES ON COURSE

NOTES ON COURSE

NOTES ON COURSE

NOTES ON COURSE

Classroom Teaching Philosophy

“What’s the scandal of this text?” This is the question I always ask during the first discussion of a work in my smaller intellectual history or literature seminar classes. Because I see it as my role to introduce my students to the extended conversation that comprises academic tradition with which they must engage, we must highlight the ways in which important texts challenge or upend conventions or assumptions while partaking in an intellectual history. The question “What’s the scandal?” thus marks a trajectory of learning in general, wherein new experiences break up and reformulate the students’ own body of knowledge. I understand my roles as literary scholar and teacher and language instructor as inseparable. Teaching and the study of languages necessarily extend beyond the context of rote vocabulary and grammar exercises and into a greater cultural context and the study of literature necessarily depends on strict attention to the use of language through detailed close readings.

I have designed my literature and philosophy classes so that they span epochs and theoretical discourses in order to deepen an understanding of a cultural tradition. In “The Failure of Human Dignity: Human Rights, Literature, and Philosophy in the long 19th Century,” for example, we attended to 19th- and early-20th century canonical texts and placed them into dialog with contemporary philosophical reflections in order to explore the problems inherent within human rights. In “Contemporary Perspectives on Kafka’s Prose,” I introduced Kafka’s work through multiple historical, cultural, philosophical, and political perspectives. The course addressed Kafka’s work along with the critical trajectories it has initiated and works of literature, art, and film it has inspired. By crossing disciplinary boundaries, my courses encourage students to recognize both the ruptures and continuities between the Enlightenment and today in a wide analysis of cultural forces and intellectual history.

I am a proponent of active learning and create a welcoming class atmosphere that allows students to feel at ease and to participate with confidence. I encourage students to feel empowered to take responsibility for their own learning by preparing questions for each class that, along with frequent response papers, are designed to promote class discussion. I then frequently restrict the discussion temporarily to short excerpts, which allows me to demonstrate how a close reading of one piece of the text can lead to greater insights into the whole. Another exercise I have found particularly illuminating is having students work in groups to produce a paraphrase of an important passage. My students always believe this to be a simple task, but they soon discover that it requires a thorough understanding of both the original text’s argument and its use of language.

Because literary study is also about finding the seams and joints of writing and language, the experience of teaching language reinforces and improves my effectiveness in all of my classes. I have taught all levels of German language in both intensive and standard settings. I practice a learner-centered, communicative approach that emphasizes interaction and dialog while nevertheless stressing oral and written proficiency and grammatical rigor. Thus I have two basic goals in teaching language. The first and primary goal is to make my students proficient in the German language, which requires pedagogical methods and clear objectives in each course. The second, concomitant goal is to foster enthusiasm for German culture and history that maintains the joy of learning a foreign language. Beginning with the first elementary German classes, literature and other cultural materials provide students with access to the rhythm and sound of German as it is connected to life and thought in the German-speaking world. I hope to transmit to my students not only my knowledge but also my curiosity and enthusiasm for the subject matter.

It is crucial, however, that students find this enthusiasm within themselves. The process of learning a language must engage the student on a personal level, and the learning experience must encompass not only the culture and history of the language being learned, but also the lives of the students learning it. The format of foreign language classes is unique, for it reveals that this communication is often imperfect, and does not always occur within the given confines of syllabi and course descriptions. It can also be a frustrating and frightening environment and it is my job to create an environment in which each student feels his or her participation is both sought and valued, regardless of level of ability. Not all students learn in the same way, however, and I firmly believe that a teacher’s greatest asset is flexibility. To that end, I consider time spent in office hours to be a crucial part of instruction. In them, I can get a better grasp of each student’s needs and interests while being able to address any individual difficulties. This process ensures that each class is unique even when covering similar material.